La Paz Through Glass

Scenes of Bolivia's capital at night from a car and some thoughts on the place

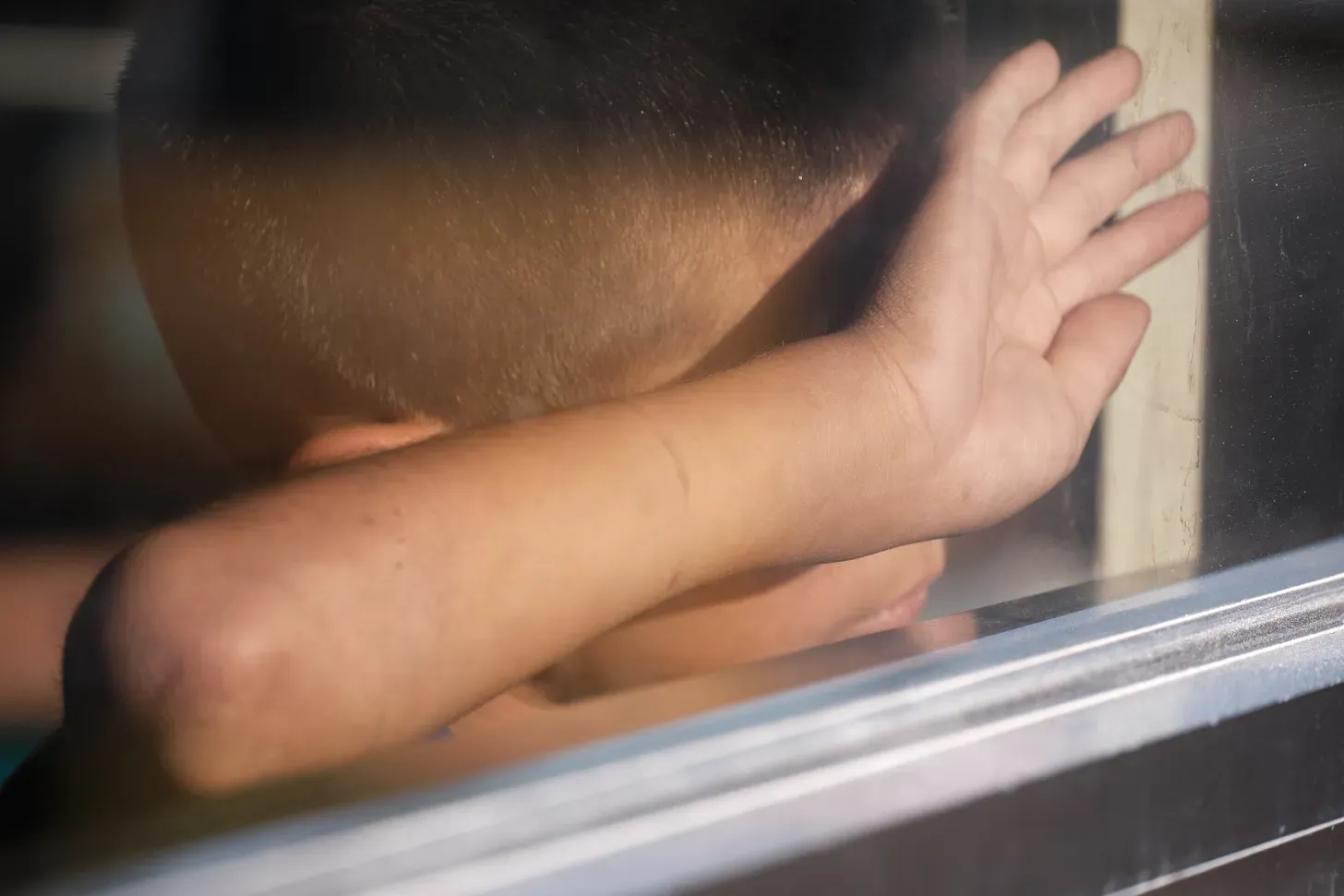

I went to La Paz convinced I was about to take my best photo ever: a crowd of tightly packed emotive faces in motion framed through a car window and intensified with hard flash (I explain this idea in more detail later in the post). There was no reason this photo had to be made in La Paz, but the city’s austere backgrounds and hectic street life would facilitate it. The only better places for this kind of photo were in the African and South Asian megacities, but I didn’t have the resources to get there.

My arrival in La Paz seemed to confirm my high expectations.The noisy streets were filled with colorful, driver-customized public transport buses/vans and swarms of determined commuters moving between—many of them women wearing bowler hats and vibrant Aymara and Quechua dresses that pop off the city’s mostly muted tones.

What’s more, La Paz was walkable and very urban, unlike so many cities in the Americas. I was thrilled. Not only was I going to take my best photo ever, but I was going to have a blast living in La Paz until then.

Over the next week, I spent my time meeting up with local photographers and journalists, looking for a driver, and exploring the city by foot. I met some lovely people and the city continued to amaze me visually, especially as seen from the extensive cable car system. Still, something was off. Despite all the hustle and bustle, La Paz felt empty. It felt like I was walking through a simulation, like some far-off Grand Theft Auto map set in Latin America. The longer I lived there, the more I walked, the more markets I visited, the emptier the city felt.

I can’t say I hadn’t been warned. I spent my first week in Bolivia in Santa Cruz, the country’s lesser known but richer and more Mestizo big city in the swampy low-lands. There, everyone I told about my plans for La Paz, including many transplants from La Paz, cautioned me that people in the capital were cold and closed off. But I just wrote off the Cruceño’s characterizations of Paceños as a product of big city rivalry and anti-indigenous racism—both which are palpable in Santa Cruz. As for the Paceños who told me I wouldn’t make friends in their city, I guess I ignored them.

Alas the reserved altiplano culture is real and it does make La Paz a much lonelier place than it seems on the surface. Nowhere is this paradox more striking than in the city’s giant open air markets. They look like monuments to Latin American vibrance: colors, every sort of produce imaginable, mummified llama fetuses to be used in ritual sacrifice, music blasting. Yet the vendors and their many clients don’t talk to you, they don’t even look at you. And it’s not just you, the lone gringo—they aren’t talking to each other either. It’s as if Helsinki and Mexico City had a baby.

I don’t hold it against the Paceños. I don’t approach every capri-wearing German tourist I see in my home city to ask them where they’re from, how I can find them on facebook, and if they’d like to come get drunk at my niece’s elementary school graduation party over the weekend. But I like to visit places where the locals do that to me.

I was feeling pretty blue by the time I found a driver (more on the great Ahmed in this series’ next El Alto installment). I’d like to think the photos I took owe their melancholic quality to my psychological state, but I’m not sure that’s true. It’s possible that taking photos of pedestrians from inside a car will always yield sad photos, no matter how happy the photographer is. What I do know is that I didn’t take my best photo ever in La Paz and that is at least partially due to my unhappiness there—the 8-year-old point and shoot camera also didn’t help.

After about a month in La Paz, and maybe 10-days taking these photos with the help of Ahmed, I decided I couldn’t take it any longer. Maybe that photo was around the corner, but it didn’t matter. I had to get out of La Paz.

Where this came from and where it's going

My obsession with glass started six years ago, just as I was getting into photography. I’m not a good enough writer to explain what’s so special about photos through glass, but if you like my photos you get it.

Back when I lived in El Paso, I used a 84-305mm-equivalent zoom to take candid portraits of people in their cars and at different bus stations around the city. At the time, I was convinced these were the photos I wanted to make. Looking back on it though, they were probably the only decent photos I was capable of. I hadn’t developed the soft skills, timing and visual know-how to make sense of non-static environments with a wide-angle lens. Still, some of those photos still seem powerful to me.

I spent a couple years working in Mexico after El Paso and forgot all about glass. But then I moved to Moldova for a Fulbright project and it came roaring back into my life. Maybe something about melancholic places drives me to windows. Anyway, in Moldova, and later Ukraine, I’d take photos from the inside of vans and buses to pass the time on the way to different destinations to take photos for my offical projects. Soon I realized the photos I was taking to kill time were better than the project ones.

Around this time, realizing documentary photography was unlikely to ever pay the bills alone, I started building a fashion/editorial portfolio. I’d often design scenes around windows that I’d hoped for in real life but that had never materialized. I probably went a bit overboard with the repetition. Towards the end of my time in Eastern Europe, one of my favorite models to collaborate with, Sandy, told me that she wouldn’t work with me on any more shoots involving windows.

At some point earlier this year, I had the idea to do a big series of street photos taken from vehicle windows. It would require extensive travel and take several years to complete, but I was convinced the photos would be powerful enough to turn me into a famous photographer. I went to La Paz to start the work.

My failures in La Paz discouraged me a bit. I still believe in the project idea, but it would probably take even longer than I’d thought and I’d definitely need a fancier camera—my Canon G1X iii’s single point autofocus wasn’t reliable at night and manual focus made the screen freeze up, and sometimes the shutter lagged close to a second. I don’t know if I want to commit so much time and money to a project that has no guarantee for success in the fickle art world.

But, art success or not, I think this is a cool way to see a city. So every month I’m going to ride around a different city taking photos and upload them to this blog. Next month’s installment is El Alto, Bolivia, which I promise will look very different to this one.